Jiude buqu, xinde bulai (If the old doesn’t go, the new won’t come)

A Melancholy Trip Down Memory Lane

Chengdu 1991

It was February 1991 and we had arrived the night before, after one of those long bus rides from hell, and quickly installed ourselves in the comfortable Traffic Hotel. The weather in Chengdu was cloudy and grey, the sun was never to show its face for the whole week we were there. There was a slight winter chill in the air and we kept expecting it to rain, but it never did. Our first impressions of Chengdu were not overly enthusiastic, it seemed like most other Chinese large cities at that time, drab and featureless. Sterile government buildings lined the main boulevards, a testimony to the worst of Soviet style architecture. However, as we strolled aimlessly around, it quickly became obvious that the real Chengdu was just around the corner. And literally! Diving off a main street into a side ally you would find yourself in the midst of bustling street markets, full of the hustle and bustle of frenetic street trading. Vendors sold everything from black-market jeans and watches, to bags of freshly crushed chillies and pungent pickles. Street artisans plied their ancient trades, from basket weaving to dentistry, and small home industries ground sesame oil or produced vinegar. The smell of kerosene from the impromptu food stalls filled the air. The whole city beyond the main thoroughfares heaved with tremendous vigour. Every street offered something different, enticing the curious traveller to delve in and discover something new.

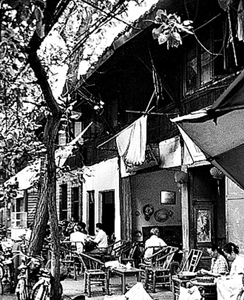

And then there were the teahouses. Some were set in the old wooden buildings with their overhanging balconies that were characteristic of old Chengdu, and they frequently spilled out onto the crowded, narrow streets. Others were tucked away in hidden courtyards, often under the cover of a huge tree, some of which grew through the roofs of the actual buildings. Though now more than 15 years have passed, I still remember cycling down ally after ally, passing countless teahouses where the young and the old sat inside and out on bamboo chairs, playing Mah-jong or Chinese Chess, with their bird cages hanging above them. Meanwhile, the teahouse owners carried huge copper kettles with enormous spouts, replenishing their customers’ tea cups with an endless stream of boiling water.

The teahouses have been popular all over China for centuries, but never more so than in the province of Sichuan and its capital Chengdu. Traditionally, the teahouses have played an important role in Chengdu society and have served as places to relax, to do business and to talk politics. Many teahouses were closed down during the heyday of the Cultural Revolution, denounced as dens of bourgeois conspiracy. They reopened again with a vengeance, during the opening-up of China in the early 1980s and once again took up their social role. Certainly, they were doing a roaring trade in the early nineties. Far from being grey and drab, they turned Chengdu into a vibrant and fascinating place.

Chengdu 2001-2006

What Teahouses?

Anyone who has visited Chengdu recently might ask: “What on earth are you talking about? What teahouses? Where are those old streets? And what about the street markets?” And you’d be right. They have gone, yes, nearly all of them. The streets with all their traditional wooden houses have been demolished, the markets have been closed down and replaced by shiny, modern supermarkets and shopping centres. Those few markets that remain are sad remnants of what there was before.

Tea is still the most popular drink in China, and in Chengdu for that matter, but the teahouses, at least the traditional ones, have come up against an enemy far more voracious than the Cultural Revolution. Modernization! Along with the markets, the teahouses have been flattened. Hapless victims of the huge urban overhaul Chengdu has undergone in recent years. According to the proud manager, the number of Starbucks’ outlets is expected to overtake the teahouses in the next couple of years.

What remains of Chengdu’s teahouse culture, is mainly concentrated in the beautiful teahouses located within the city’s many temples and parks. While these teahouses are fantastic places to while away a pleasant afternoon, for those who knew Chengdu before its modernization drive, something is missing. For me, Chengdu has lost its vibrancy and energy, its sense of history and timelessness, and that special ‘something’ that made the city stand out. It is not that Chengdu in 2006 is an unpleasant place, in fact, it is clean, modern and prosperous. The problem is that Chengdu is now an ‘anywhere in the world city’, perhaps even a little boring.

And what of the local people who frequented the teahouses? For them, the tea houses provided a space to keep up with local gossip, compete in marathon Mah-jong sessions or Chinese Chess, discuss the health of their birds and, most importantly of all, have human contact, something so important in Chinese society. I have often wondered where such people go when their local teahouses disappear. I suspect that, like the teahouses, their own houses are being demolished too, and they are moved out to some new housing estate, inconveniently located far from the centre of the city, where human communication is more difficult.

‘Jiude buqu, xinde bulai’

Am I being too romantic? It is a question I have often asked myself, when witnessing the destruction of old Chinese architecture. After all, living conditions in those old wooden buildings must have been quite grim, especially in the damp winter months. Are the Chinese quite happy to see the back of them? After all, as the Chinese saying goes, ‘jiude buqu, xinde bulai’, meaning, if the old doesn’t go, the new won’t come. It cannot be denied that the new coffee houses, shopping centre restaurants and snack bars offer a wider choice than just “Tea”. We are always told that choice is important and I suppose the Chinese want to have that choice too. However, I can’t help feeling that these anonymous places that have replaced the old teahouses, and the new buildings that have sprung up from the ashes of the traditional streets, have left Chengdu devoid of its essence and from what distinguished it, not only from other cities in China, but from the rest of the world. The modern Chengdu is identical to any other well-to-do Chinese city. Maybe that’s what its residents wanted? I don’t know, but I’m not so sure.

In the second of three stories that make up his book “Wild Grass”, the journalist Ian Johnson describes the struggle of a few people who try to protect what is left of Beijing’s historical centre and its traditional courtyard houses, or Hutongs. Their battle is a lost cause, and Johnson’s gripping description reveals the total insanity and corruption that has characterised urban development in Chinese cities in recent years. At the same time, he gives testimony to the bravery of those few people who have tried to stand up and protect China’s heritage, as well as their own homes. What stands out most in Johnson’s account, is the love and respect these people feel for their often decrepit ancient homes, and how attached they are to their neighbourhoods. Moreover, Johnson quite rightly points out that the so-called ‘choice’ the government gave them, was a complete fallacy. When asked whether they wished to stay in their old houses, or move to brand-new ones, most residents obviously opted for the second. However, the real ‘choice’, which would have meant deciding whether to stay in their own, restored and rehabilitated old homes, or to move into some hastily constructed, ramshackle tower blocks, far from the centre, was never given. As many of these former Hutong residents have found out since, their new homes were built with inferior materials, miles away from their friends and neighbours, their work places, health care and leisure centres, or any other facilities.

Did the same struggles take place in Chengdu? Are there stories of local heroes that will never be told, who fought against all odds to defend the Chengdu teahouse and the wooden houses? And if they did, what happened to them?

Conclusion

One interesting contradiction is that the one remaining old street in Chengdu, Kuan Xiangzi, which still harbours some traditional architecture, now attracts more Chinese tourists than Westerners, nostalgic for their past. On our last visit (August 2006), Kuan Xiangzi was undergoing a complex transformation, midway between a restoration and a demolition. It was difficult to know which side would win. The final outcome may well be another instance of the Chinese speciality of destroying ancient historical buildings, only to reconstruct them again in the same style, what one might call ‘new old buildings’. I think the words of a friend of mine from Chengdu poignantly sum up the feelings that inspired this article. He once told me sadly: “My son will never know the old Chengdu, I can only tell him about it, because by the time he grows up, there will be nothing left to show him”.