PRC and The Soviet Union. This Essay was written for the course: China and International Politics. As part of my MSC at SOAS.

Adam Mayo

China and International Politics

15/12/1999

Was an alliance between the PRC and The Soviet Union inevitable?

This paper will argue that the Sino-Soviet alliance was inevitable. Following the overthrow of the nationalist regime in 1949 Mao Tze-tung (Mao) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) wanted and sought an alliance with the Soviet Union. There were ideological, strategic, economic and personal reasons why Mao leaned towards the Soviet Union.

Recent evidence points to the fact that there was never a possibility that Mao would lean in any other direction and especially not to the American camp. However, an overview of the historical relationship between the Soviet Union and the CCP reveals that there were a number of underlying tensions between the two sides that might have suggested an alliance was far from inevitable and may have been a surprise. It may also be argued, that the alliance was achieved by papering over the cracks in Sino-Soviet relations. Therefore this paper will be divided into two parts. The first part starts with an historical analysis of the tumultuous relationship between the future allies up until the end of the war with Japan. Two important theories will be debated. Firstly, was Mao trying to keep the CCP from Moscow’s dominance? Secondly, how antagonistic were relations between the Mao and Stalin? The second part will analyse how Marxist ideology was always going to drive the CCP into the Soviet Camp and why it was inevitable that relations between the CCP and America would become estranged in a new world order where neutrality was impossible.

Part 1

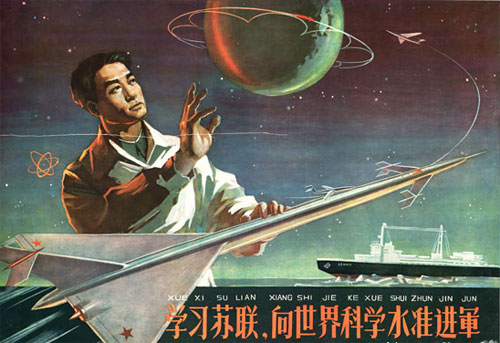

PRC and The Soviet Union: The First United Front and the Jianxi Soviet

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s the Soviet Union attempted to subordinate the CCP to the control of the Communist International, the Comintern. In turn, the Comintern became a tool with which Stalin enforced the internationalist line laid down by Moscow. A major element of the internationalist policy was to follow Lenin’s theory that fledgling Communist movements in colonial or semi-colonial countries had to form a united front with national liberation movements despite their bourgeois character. The aim was that the communists would then seize control of the nationalist movements from within. In the case of China this meant the Comintern bringing the CCP into an alliance with the Kuomingdung (KMT).

The First United Front ended in a total disaster, and almost led to the annihilation of the CCP. A mixture of Chiang Kai Shek’s refusal to play by the Comintern rules, and the Comintern tactics based on Stalin’s misinterpretations of events played a major part in the debacle. However, Stalin managed to make the CCP leader Chen Tu-hsiu a scapegoat for the failure of his own Policies. Interestingly, Chen had been sceptical of the alliance.

Having been forced to retreat into China’s remote hinterland, Mao began his experiment with rural soviets. By 1931 a large part of the CCP, including the Red Army was outside of Moscow’s control, and Mao was only paying lip service to orders from the underground and ineffectual Moscow backed Party Central Committee in Shanghai. During the Jianxi Soviet period, Mao was able to put into practice both his ideas on peasant mobilization, land reform, and guerrilla tactics. However, when the situation in Shanghai became untenable, the entire leadership of the CCP moved on mass to the Jianxi Soviet.

Moscow sent twenty-eight trained Chinese cadres under the leadership of Wang Ming to regain control of the party apparatus and contest Mao’s position (Dittmer, 1992, p. 4). With the arrival of the Twenty-eight Bolsheviks, Mao’s ranking in the party hierarchy appears to have been seriously undermined, especially during the later Jianxi period. While at the same time his rural experiment became the subject of leftist excesses. In addition, the Comitern military advisors also reversed Mao’s previously successful guerrilla tactics for more conventional military tactics. The result was the destruction of the Jiangxi Soviet and the start of the Long March.

The Impact upon Mao and the CCP of the continued failure of Moscow inspired internationalist interventions between 1927 and 1935 cannot be underestimated. At the same time Mao had radically turned Marxist-Leninism on its head. The peasants and not the industrial proletariat had become the vanguard of the revolution. Mao had Sinicized Marxism and made it “…specific to Chinese characteristics :”( Dittmer, 1992, p.4). Furthermore, among Mao and his followers in the CCP, a determination sprung up not to allow the party to become subjected to complete Soviet domination (Ibid).

PRC and The Soviet Union: Mao’s leadership and the Second United Front

The following period covers the Second United Front and the war against Japan. The key issues during this phase were over Mao’s leadership that he won during the Long March, Mao’s continuing battle with the internationalists in the CCP, the policy of the Second United Front, and whether Mao was strictly obeying Stalin’s orders or trying to loosen Moscow’s hold on the CCP. Two different interpretations of events will be analysed. The events surrounding Mao’s rise to power in the CCP during the Long March and the subsequent Moscow instigated Second United Front with the KMT have become subject to much debate in recent years as new information has come to light. Much of this information has direct bearing on how Soviet Union and CCP developed between 1935 and 1949.

Micheal Sheng has argued that Mao not only received full support from the Comintern during the leftist deviation period at Jiangxi but also during the period when Wang Ming and the internationalists were launching full speed into the Moscow backed United Front with the KMT. Sheng also tries to dispel the myth that Mao rose to power without Soviet endorsement by arguing that Mao didn’t take advantage of the break in radio contact with Moscow at the Lunyi Conference in order to assume control of the Party by Stealth. Sheng suggests that as soon as it was possible, Mao endeavoured to restore radio links to convey to Stalin the new situation (Sheng, 1992, p.151-153).

John Garver does not support the above view of events. First of all, Garver argues, that Mao won the leadership of the CCP if not in the face of Comintern opposition, he at least won it without Comintern support (Garver,1988, p.10-13). Garver suggests that Mao did indeed take advantage of the break in radio contact with Moscow to take control of the party. After all, Mao had been removed from his position as a top-level leader of the party in 1934 just prior to the Long March (Garver,1988, p.13) and could have expected Soviet opposition to his rise.

There is further disagreement between Sheng and Garver over the degree of discrepancies between the CCP and Moscow on the issue of the Second United Front. According to Garver, Mao was far more opposed to an alliance with Chiang Kai Shek than the Comintern and wanted to continue the armed struggle against the KMT (Garver, 1988, p.171). In addition, Garver argues, that the Soviet Union feared that the CCP might provoke Japan as well as undermining Soviet–KMT diplomacy. Sheng’s point is that Mao’s central concern was the armed struggle but he tried to combine it with the United Front, Sheng claims that some of the internationalists in the CCP harboured even deeper anti-Chiang sentiments than Mao. It was Mao after all who carried out Stalin’s instructions (Sheng, 1992, p.150/159/165). What does become clear is that the Soviet Union had to reign in the CCP in order to cement the anti-Japanese alliance; the Xian incident is a prime example. Stalin’s reasons for forming an anti-Japanese alliance with the KMT did make strategic sense, given the military weakness and geographical isolation of the CCP in 1935/36. It would also not be the last time that the Soviet Union would put its own interests ahead of those of the CCP.

During the anti-Japanese struggle Mao again had to battle with the internationalists in the CCP, According to Garver, Mao feared that the internationalists wished to once again subordinate the CCP to complete Moscow control (Garver, 1988, p.276). Garver argues that the German invasion of the Soviet Union gave Mao the room he needed to loosen the shackles of Soviet domination over the CCP. Just as he had done at Zunyi, Mao took advantage of the changed situation and Moscow’s distractions. The fact that the Rectification Campaign of 1942 (Zheng Feng) was launched during this period lends credence to Garver’s argument. Mao purged many of his opponents during this campaign and gained a free reign again in the CCP while weakening the position of the internationalists (Garver, 1988, p. 274).

Garver has again challenged Sheng on a number of points over the CCP-Moscow relationship during the Second United Front. Garver admits that Mao never sought to openly reject the Comintern, neither was he antagonistic or confrontational towards it. Mao was too aware of the need not to alienate the Soviet Union. First of all because he needed their aid, no matter how little it was. Secondly, Garver claims Mao saw a time when the Soviet Union would be an ally helping to liberate China. However, Graver also adds that Mao interpreted Moscow’s directives as he saw fit, believing that Moscow was out of touch with Chinese realities (Garver, 1992, p.177). Mao’s aim was the expansion of revolutionary power and past experience had taught him that Moscow’s lack of understanding of the situation on the ground in China could result in disaster. On this evidence it would appear that Mao was a “master of deception” (Garver,1988, p.274) by giving a public image of loyalty to Moscow on the one hand, and defying comintern directives on the other hand. Garver’s overriding point is that Mao was both a revolutionary and an ardent Chinese nationalist. Stalin believed Mao could become a loyal internationalist and what Stalin didn’t know was that Mao would “…ultimately emancipate the CCP from Moscow’s Control”(Garver, 1992, p.173).

Sheng argues, that Garver is wrong to put Mao in the Category of a dissident Communist, who defied Stalin and defeated the Internationalists led by Wang Ming, while conducting the diplomacy of Chinese nationalism with Moscow. Firstly, Sheng claims that Mao was sensitive to rather than confrontational with Moscow. Their differences were of “emphasis rather than substance” (Sheng, 1992, p.150). He also suggests that the relations between Stalin and Mao were harmonious and that Mao was responsive and amiable towards Stalin’s advice (Sheng, 1992, p.181). Sheng’s point here is that Stalin’s role in the development of the CCP wartime strategy was important and constructive and Mao was generally obedient to Moscow’s directives.

PRC and The Soviet Union: Conclusion Part 1

Two major issues arose from the first period of contact between the CCP and the Soviet Union. Firstly, there was the attempt by Mao and his supporters in the CCP to maintain a degree of independence from Moscow. Secondly, there was the need to adhere to the discipline of the international socialist line. The early disasters of the CCP under the guidance of the Comintern made Mao and other members of the CCP suspicious of Moscow’s ability to understand Chinese realities. Garver is right to point out that Mao wanted to keep the CCP free from Moscow’s domination. A large part of that struggle appears to have been waged against those, who, like Wang Ming and the internationalists were contending for power in the CCP. However, Garver over emphasises the animosity between Mao and Stalin, in fact Mao derived a lot of his legitimacy from Stalin, and Sheng is right to suggest that many of their differences were of emphasis rather than substance. Part two will analyse how these two contending Strands developed as result of the changed international environment in the aftermath of the Second World War.

Part 2

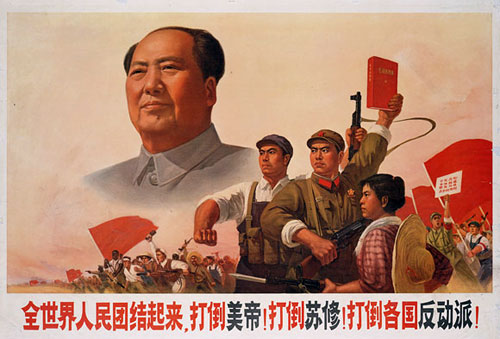

PRC and The Soviet Union: The New World Order

The end of the war in Europe and with Japan in Asia ushered in a new era in world politics. The two wartime allies, the United States and the Soviet Union, had become the dominant contending powers in a bipolar conflict that saw them bitterly divided by ideology and strategic concerns. It was world in which other nations had to choose between one side and the other. Zhdanov’s speech at Wiliza Gora in 1947 set the tone for international relations in the Cold War era by dividing the world into two camps. There was the “imperialist and antidemocratic” camp, headed by the United States and the capitalist world, and there was the “democratic and anti-imperialist” camp which was led by the Soviet Union, and included the Communist countries of Eastern Europe, and colonies well on there way to independence (McLane, 1966, p.353).

Stalin’s oriental specialist Zhukov applied Zhdanov’s thesis to the East. Firstly, he emphasised that the Soviet Union was in the same camp as the national liberation movements. Secondly, and crucially, on the issue of neutrality, Zhukov claimed it was only possible to be in support of the Soviet Union’s position, or to be against it (McLane, 1966, p.353-355). The following part of the Paper will argue that the CCP never doubted which side it would take and neutrality or even leaning towards the American camp was never an option.

There was speculation that in the aftermath of the Sino-Soviet alliance that events could have turned out different. In some quarters in the United States it was argued that there had been a ‘lost Chance’ with China. The argument ran that in 1945 there was a ‘window of opportunity’ for dialogue with Mao and if US policy had been more flexible and neutral it was possible that Mao could have been won over. In addition, the Americans also appear to have held out hope that Mao was more of a nationalist than a full blooded communist and that even if the CCP did come to power, China would be like an Asian Yugoslavia and keep out of Moscow’s umbrella ( Gaddis,19997, p.61/62). However, recent evidence doesn’t appear to support either of those theories.

Arguing that the “lost chance” theory was in fact a delusion, Sheng points out, that the direction in which the CCP would lean was clear even before 1945. Mao saw himself as a Marxist, and ideological ties between the CCP and Moscow predetermined the CCP’s decision to move towards the Soviet Union (Sheng,1993, p.136). In addition, Gaddis claims that the relationship between Mao and Stalin was of a fan to a superstar, with Mao being eager to receive Stalin’s recognition (Gaddis, 1997, p.66). This was in spite of all the past problems that had resulted from Stalin’s bad advise and meddling in CCP affairs. Drawing from such conclusions it becomes clear that the American experts on the ground in China appear to have been sold a false impression of the ideological disposition of the CCP.

The CCP and the United States 1945-1950

An important part of the US-CCP relationship revolved around how the CCP interpreted the war time alliance in the Anti-Japanese Struggle and what would happen when the Japanese were defeated. Mao always knew that when push came to shove the US, despite what ever differences it may have had with Chiang Kai Shek, would always come down on his Chiang’s and oppose the CCP (Sheng, (1993, p137). Events seem to have proved Mao right. The US broke assurances that they had given Mao over US neutrality in the civil war by air lifting thousands of nationalist troops to the north to head off the communist attempt to seize Manchuria. This experience left Mao feeling betrayed, and according to Gaddis, Mao swore he would not be cheated again.

However, Deception was not always one way traffic. The CCP’s wartime policy was one of extreme expediency. The false impression the US derived from the communists largely comes from the success of CCP expediency. It was a policy in which diplomacy with the US mirrored the formation of a United Front with the KMT. Both were tactical short-term objectives that subordinated the revolutionary struggle until it was time to renew it again (Sheng, 1993, p.136). As Sheng points out, for Mao “…anti-imperialism was an extension of the class struggle paradigm” (Ibid). The principal objective of the CCP was to win over the American officials and citizens at Yenan by trying to convince them that the CCP was not a Communist party in the same mould as the Russian equivalent. New Democracy, not Communism was emphasised, and formal ties between Moscow and Yenan were denied. It was hoped that the US would become convinced that the CCP wanted good relations and that they were a party of moderates and not communists at all. The goal of this policy was for liberal opinion in the US to put pressure on the US government in order to persuade the KMT to stop its attacks on the CCP (Shum, 1988, p.226-227). There were too many hawks in the Truman administration to buy the whole CCP yarn. However, confusion in American assessments of the CCP in the ensuing years, certainly seems to have been influenced by the image that the CCP was able portray. US policy does not seem to have predicted that the CCP would lean towards Moscow.

Once ties between the US and the CCP had begun to deteriorate Mao became convinced from 1946 onwards that the US would openly intervene in China’s civil war on the side of the KTM. Mao mistakenly thought China was the centre of the US theatre of operations. According to Gaddis nothing could have been further from the truth, but Mao could never have understood that China was on the periphery of US foreign policy priorities. Mao continued to perceive that the US would intervene in China, directly or through its ally Japan, even after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). This mistaken assumption hastened the strategic reasons for concluding an alliance with the Soviet Union.

The CCP and the Soviet Union 1945-1950

During the civil war the CCP’s relations with Moscow were somewhat strained by continued Soviet recognition of Chiang Kai shek’s regime. Stalin had believed that following the defeat of Japan, the KMT would re-instate its authority over China. Elleman suggests that Stalin’s policy was even more cynical than first thought and that the Soviet Union resorted to playing off the KMT and the CCP against each other in order to gain territorial concessions. Stalin wanted to separate Outer Mongolia from China, and in order to do so he promised Chiang Kai Shek that if he signed away Chinese Suzerainty over Outer Mongolia, the Soviet Union wouldn’t help the communists. As soon as the nationalist regime acquiesced in January 1946, the Soviet Union turned its support to Mao (Elleman, 1997, p.245-247). Elleman has argued, that the Soviet Union, through secret protocol, conducted an imperialist policy in China on a scale almost equal to that of the Japanese and the Tsarist regime before it (Elleman, 1997, p.247/285). The USSR took control of 600,000 square miles of Chinese territory and Elleman points out, that only after coming to power did Mao realise the extent of Soviet imperialism (Ibid, p.247).

Certainly some of Stalin’s actions during this period must have sent mixed signals to the CCP. First of all, after Soviet forces liberated Manchuria from the Japanese, they handed over surrendered Japanese weapons to the communists, and then proceeded to strip Manchuria of its entire industrial base and cart it back to the Soviet Union.

Secondly, Stalin was surprised by the swiftness of the communist successes on the battlefield in 1949 and feared that the Chinese civil war would “…overturn the spheres of influence arrangement set up at Yalta and lead to a United States intervention in China” (Garver, 1990, p.303). The spectre of a conflict with the US in China for which the Soviet Union was not prepared, led Stalin to warn Mao against driving south of the Yangtse (Gaddis, 1997, p.65). Stalin tried to manipulate Mao’s fears of US intervention. Advise that Mao ignored. Again the Soviet Union’s national interests took priority over those of the Chinese communists. Zhou En-lai even feared that China might be partitioned into North and South like Korea (Garver,1990, p.303).

Despite so much Soviet duplicity and CCP misgivings over Soviet strategy, the CCP continued to adhere to the “…discipline of international democratic centralism,” (Dittmer, 1991, p.210). Neutrality was never really an option for the PRC. The perceived threat from the US and the need for China to rebuild its economy meant it had to lean towards the Soviet Union. Mao saw in the Soviet economic model, the opportunity to use the same techniques to transform China. Undoubtedly this would involve a transfer of technology and expertise. The fact that contemporary economic growth was superior in the Communist counties in Eastern Europe than in their Western counterparts may also have been influential in convincing Mao that socialist economic development was the right route to take.

The speed with which the PRC and the Soviet Union entered into negotiations in the aftermath of the communists’ victory is evidence that an alliance was being sought. The attitude of the Chinese Communists is clear from the statements made in 1949 when Mao announced that he was going to join the Soviet camp. This position was re-enforced by Deng Xiao Peng’s comments, explaining that it was better to join an alliance voluntarily, and on their own initiative rather than be forced into one in the future (Gaddis, 1997, p.65/66). The Soviet Union was initially cautious to the PRC overtures; after all they did not control the Chinese Communists as they did the communist parties in Eastern Europe, but then welcomed the PRC into their camp. As Gaddis points out world communism would be stronger with the inclusion of the PRC and it would seem that that the inherent dangers in such a treaty would outweigh the alternatives (Ibid, p.69).

Conclusion

The Sino-Soviet alliance was inevitable. On the one hand Marxist ideology ensured that Mao wanted to be in the Soviet camp, and on the other, the Cold war balance of power realities meant both countries realised the advantages of facing the perceived if not real US threat together. However, it is impossible not to come to the conclusion that this was unnatural alliance. So many underlying tensions had been covered up under the discipline of Marxist rhetoric and socialist solidarity, the issue of Outer Mongolia was never mentioned in the 1950 friendship treaty (Elleman,1997, p.245). After Stalin’s death, relations between the two communist giants fell apart.

The bitter experiences and double standards that the CCP and China as a whole had had to suffer at the hands of the Soviet Union during the inter-war years, and the revolutionary struggle exploded into a diatribe of bitter recriminations. As Adam Ulam pointed out, “The Chinese pitilessly dissect the selfish and nationalist motivations hidden beneath the Soviets language of international solidarity and devotion to the Soviet camp” (Ulam, 1976, p.681). The Sino-Soviet alliance was inevitable; its break up may have been equally inevitable.

Bibliography:

Books:

Dittmer,L. (1992), Sino-Soviet Normalization and its International Implications, 1945-1990, (Seattle, University of Washington Press).

Elleman, B, A. (1997), Diplomacy and Deception, The secret History of Sino-Soviet Diplomatic Relations, 1917-1927, (NewYork, M.E. Sharpe).

Gaddis,J,L. (1997), We Now Know, Rethinking the Cold War, (New York, Oxford University Press).

Garver,J,W. (1988), Chinese-Soviet Relations 1937-1945, The Diplomacy of Chinese Nationalism, (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

Gray, J. (1990), Rebellions And Revolutions: China From The 1800s To The 1980s, (New York, Oxford University press).

McLane,C,B. (1966), Soviet Strategies in SouthEast Asia, (Princeton, Princeton University Press).

Shum Kui-Kwong. (1988), The Chinese Communists’ Road to Power: The Anti-Japanese National United Front, 1935-1945, (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

Ulam, A,B. (1976), Expansion and Coexistence, Soviet foreign Policy, 1917-1973, 2ed. (New York, Preager).

Whiting, A, S. (1980), China Crosses The Yalu, The Decision To Enter the Korean War, (California, Stanford University Press).

Womack, B. (1991), Contemporary Chinese Politics in Historical Perspective, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

Articles:

Garver, J,W. “ Mao, The Comintern and the Second United Front.” The China Quarterly, No.129 (March 1992).

Garver,J,W. “New Light On Sino-Soviet Relations: The Memoirs of China’s Ambassador For Moscow 1955-62.” The China Quarterly, No.122 (June 1990).

Sheng, M. “America’s Lost Chance in China? A Re-appraisal of the Chinese Communist Policy towards the United State before 1945.” The Australian Journal of Foreign Affairs, No. 29 (1993).

Sheng, M. “Mao, Stalin, and the Formation of the Anti-Japanese United front: 1935-37.” The China quarterly, No.129 (March, 1992).

Sheng, M. “Mao, Stalin: Adversaries or Comrades?” The China Quarterly, No. 129 (March 1992).

Hurrah, that’s what I was looking for, what a information! existing here at this web site, thanks admin of this site.