The Rumour /道听途说 Ruili 瑞丽 is open!

Ruili is open 1991 a little known town in South-wast China suddenly became the coolest place to be.

Gweilo or gwailou (Chinese: 鬼佬; Cantonese gwáilóu, pronounced [kʷɐ̌i lǒu] is a common Cantonese slang term and ethnic slur for Westerners.

The rumour spread like wildfire around the gweilo* hangout cafes in Dali: Ruili 瑞丽 was now open to foreigners. Margie and I looked at a map and thought:’ why not give it a go?’

Ruili is open 1991 and China in 1991

China in 1990 was a very different place. Many areas still remained firmly shut to Western visitors, which is why the opening of any of these previously closed off areas caused an immediate stir in the small backpackers’ community. Travellers trying to ‘out-travel’ each other would excitedly head for these newly opened areas, chasing adventures and cool anecdotes to share in the next gweilo café they’d find themselves in.

Ruili is open 1991 and Getting there

Deciding to go to Ruili 瑞丽 was one thing. Actually getting there quite another: in those days Ruili was a two day bus ride away from Xiguan 下关 / Dali City大理, with the bus overnighting in Baoshan 保山.

It is difficult to remember everything from the long trip down to Ruili 瑞丽, but I remember the incredibly polluted river running out of Xiguan 下关 and passing through several rural markets. And I’ll never forget the incredulous faces of the receptionists at the Baoshan transport hotel保山交通宾馆 when two foreigners joined the other Chinese passengers for the overnight check in.

Heading to the Burmese border

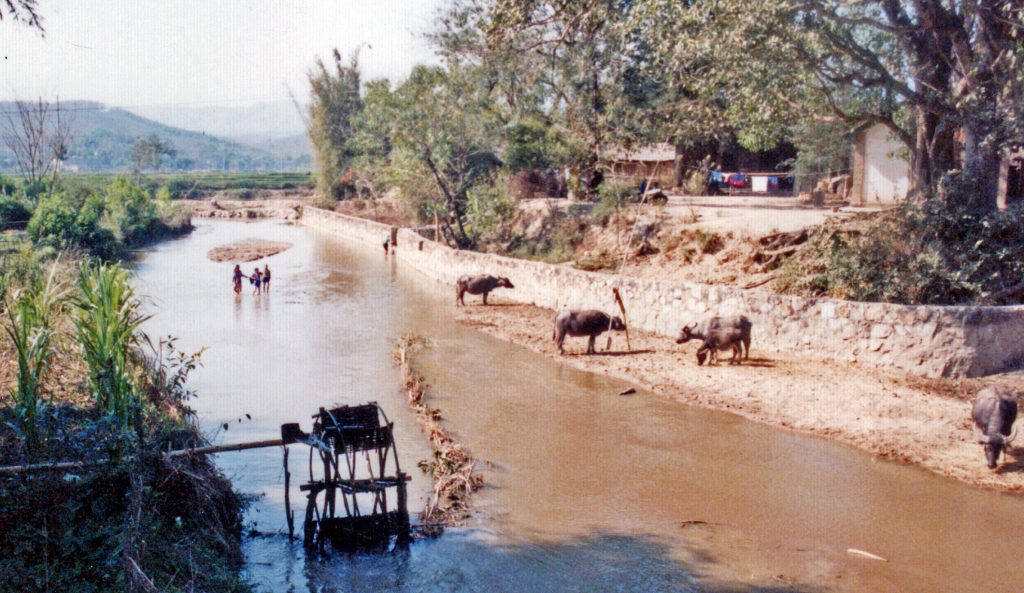

Descending rapidly after Baoshan 保山, the road then crosses the Nujiang 怒江 / Salween River and you can begin to smell and feel the sweltering heat of sub-tropical South East Asia.

I remember a strange incident at a check point just before crossing the Nujiang River: Military Police, obviously looking for drugs or other illegal goods, boarded the bus and almost took it apart; nuts, bolts and all. They then dragged a passenger, a young soldier, off the bus and gave him a vicious beating, before dumping him back on the bus. At one point, I feared he would never be seen again.

Ruili is open 1991. Arriving in Ruili 瑞丽

We eventually arrived in Ruili at 12.00 midnight on the second day and no sooner had we got off the bus than we noticed there was something different about this town. In spite of the lateness of the hour, the whole place was buzzing: bars, restaurants and dodgy ‘massage parlors’ were all doing a brisk trade. The streets were filled with Chinese, Burmese and ethnic minorities milling around the open shops and street markets where hawkers were still touting their wares. Welcome to Ruili, 1991.

All this nocturnal activity was in stark contrast to the rest of China: in 1990 /91, even in Beijing 北京 and Shanghai 上海, such nightlife as there was, mostly packed up before 20.30. Ruili seemed to be on another planet altogether!

Ruili is open 1991. Finding a Hotel

We checked into a brand new hotel, only to find it was so new that there was no running water and only the reception area was connected to the electricity mains. The following day, we escaped at the break of dawn and managed to track down the modest Ruili Binguan 瑞丽宾馆, where we bagged a cheap dorm room and where, to our immense surprise, we bumped into Glen and Lisa, an American couple we had met in Lijiang 丽江 a few weeks earlier. In fact, it turned out that the 4 of us were the only gweilos in town.

Ruili is open 1991. What to do or see in Ruili?

That was precisely the question. As Ruili wasn’t mentioned in any guide book (we were using Lonely Planet China, version 2) we set about trying to find the sights. Luckily, Glen and Lisa, who had taught English in Taiwan, could speak some Chinese,. After questioning the bewildered locals as to what we should see, we soon discovered that the actual sights were somewhat underwhelming.

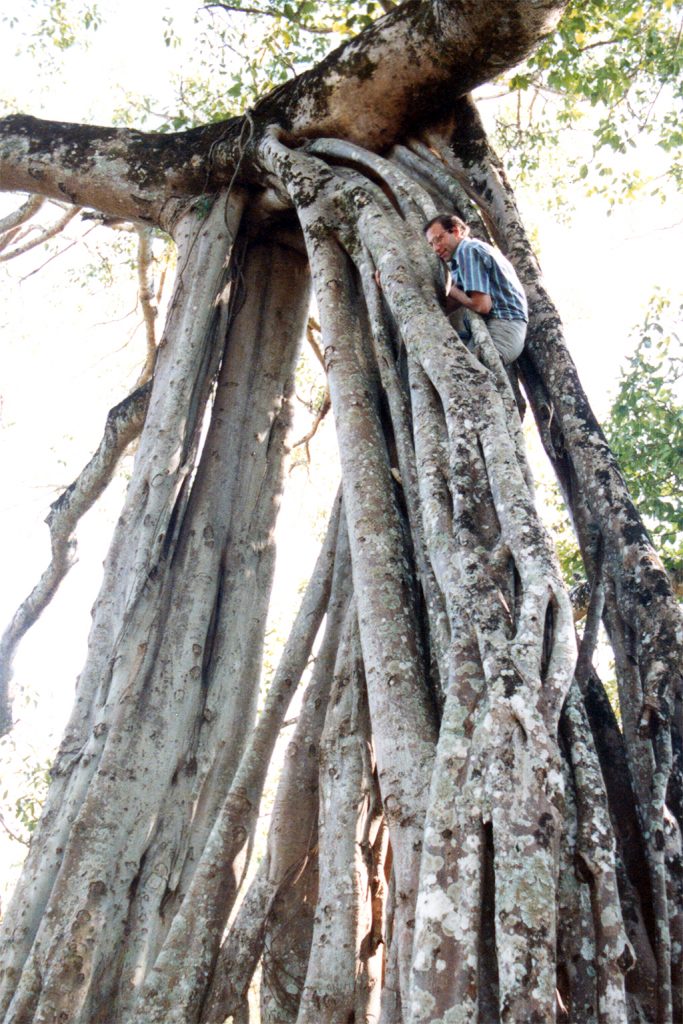

A pagoda here, a huge banyan tree there, and the Burmese border crossing were about all the tips we could get from anyone.

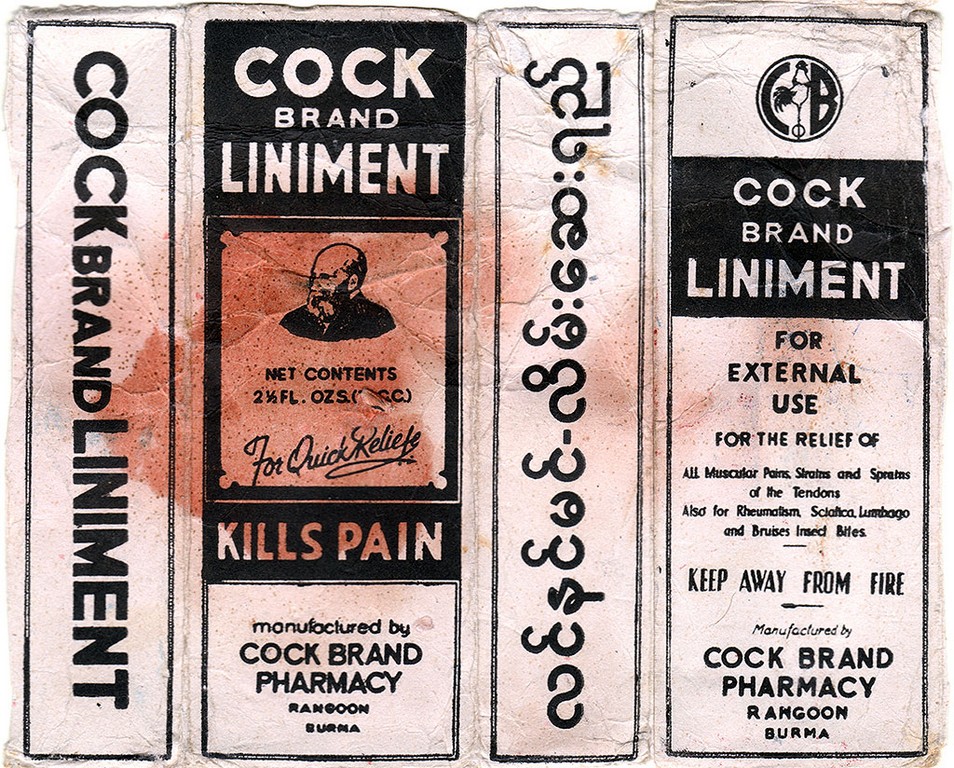

Undoubtedly, the most interesting thing about Ruili was the incredible mix of people on its streets, the colourful markets and, why not, the sleazy, seedy ambience that hinted at clandestine wheeling and dealings.

Wet Markets

Among the more exotic of Ruili’s various dodgy businesses were the wet markets (live animal markets), where the usual suspects blamed for causing the current Coronavirus outbreak and the previous SARS epidemic could be found in cages, waiting for the wok: cats, bats, rats and pangolins to name just a few.

A town with Character and Colourful Characters

Ruili in 1991 played host to jacks of all trades: Burmese Muslim merchants, jade traders, rich Chinese buyers with pretty young girls on their arm, hookers, pimps, drug dealers and addicts… and… beating them all for novelty: Kachin rebels (景颇族; Jǐngpō zú; in Chinese; members of an ethnic tribe struggling for an independent Kachin state) on rest and recreation after fighting the Burmese Junta. It was a kaleidoscope of peoples definitely worth coming all that way to see.

We found ourselves being wined and dined by rich Chinese jade dealers who seemed to think it gave them status to have Westerners at their table when negotiating with their Burmese counterparts. The whole thing was surreal and rather ridiculous.

The Burmese Influence

After all, why invite people you don’t know to a slap- up meal? They couldn’t even speak to us; they just pointed at the food and urged us to eat! In hindsight, having a cheap Burmese meal with a few cold beers in the marvelous Sweet Café would have been much more fun. But that was the kind of thing that went on in Ruili in 1991.

The Burmese Connection Sweet Café

As I mentioned before, by far the most interesting people we met were the Kachin rebel commanders, back from fighting the Burmese military Junta. They used to hang out in the Sweet Café, a real Asian hole in the wall, but with more character than any posh banquet hall.

Kachin Rebels

Some of the commanders were women, and they all spoke pretty reasonable English. They were a great source of entertainment with their stories of heroic exploits whilst fighting the Burmese army.

After its clientele, the next best thing about the Sweet Café was definitely its breakfast: milk tea, fried eggs, great fruit juices, and even Mohinga, a delicious Burmese spicy noodle soup with catfish and herbs, the perfect cure for a vicious hangover. Nowhere in China could beat the Sweet Café when it came to a tasty breakfast!

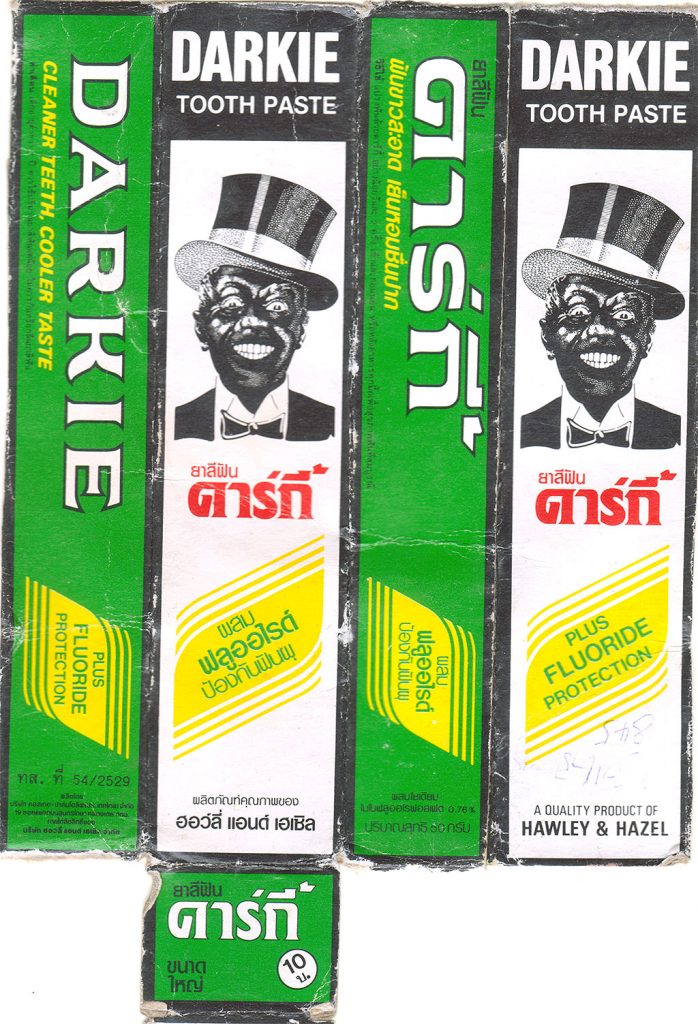

The infamous Darkie Toothpaste

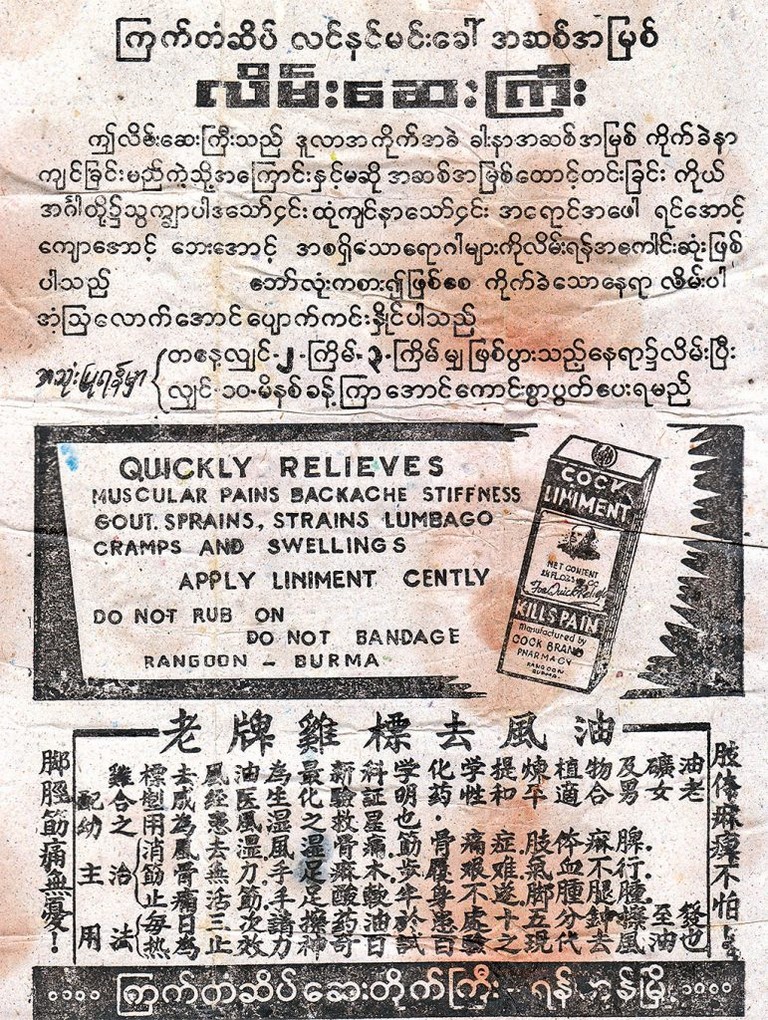

Burmese and other foreign produced products were ubiquitous in the street markets; including the infamous and totally politically incorrect Darkie toothpaste that had been renamed Darlie two years previously. Obviously, what was being sold had passed its sell by date.

The Border between China and Burma / Myanmar

And speaking of border, the border between China and Burma / Myanmar must have been pretty porous at the time, as the rebels explained that they often came to Ruili when they needed a bit of a rest. It seemed that the Chinese were turning a blind eye to their comings and goings. Actually, the Chinese authorities were turning a blind eye to almost anything happening in Ruili. But that was Ruili in 1991.

Of course, these laissez faire policies didn’t quite apply to Westerners. Some travelers told us they’d managed to sneak across the river to the town of Musé in Burma, only to get arrested and deported back to China, where they were made to write a self-criticism for having violated the laws of the People’s Republic of China. Obviously, this anecdote and the written self-criticism were worth their weight in gold, as the ultimate proof of ‘travel cool’.

And needless to say, if you did anything like this today, you’d be sent to prison. But that was then. China and Ruili in 1991 were not what they are today.

Playing Cat and Mouse with the PSB

Back then, the Chinese authorities hadn’t really worked out what to do with mischievous foreigners. It was almost as if the PSB (Chinese Internal Security) and travellers were involved in playing a good humoured game of cat and mouse with travellers pushing the boundaries between those areas that were actually open and those that were still off limits, and the PSB trying to interpret the continuously changing directives from Beijing.

Baoshan to Jinhong景洪 in Xishuangbanna 西双版纳. No Way Jose!

On our return to Baoshan we spent two hours trying to convince the local head of the PSB, who incidentally spoke impeccable English, to let us travel on by bus from Baoshan to Jinhong景洪 in Xishuangbanna 西双版纳 so as not to have to backtrack all the way to Xiaguan下关 and Kunming昆明. We studied the map together and he agreed it would be much shorter to travel direct from Baoshan 保山. However, his only answer was: “this area is closed to foreigners”. And that was the end of the matter.

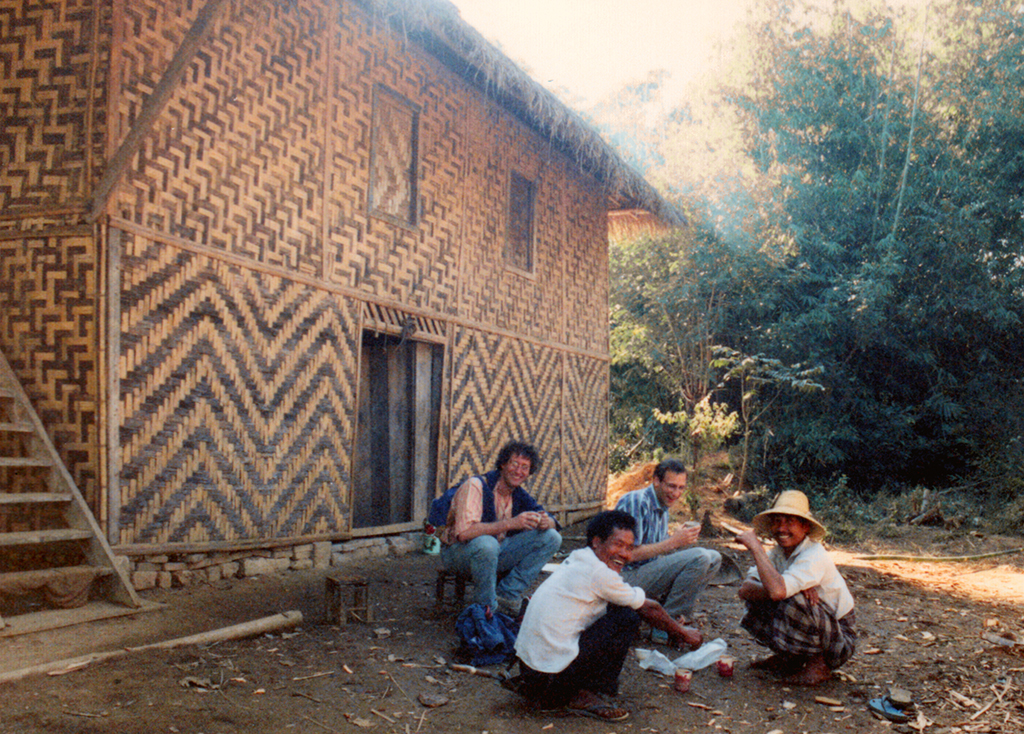

All in all we spent three days in Ruili, exploring the border area near the bridge that linked the town to Muse on the Burmese side, taking a day trip to the sleepy, non-eventful towns of Wanding 畹町 and Mangshi, playing Chinese chess with the locals, and cycling out to the nearby景颇族; Jǐngpō zú ( or Kachin); villages where we were made to feel very welcome.

Our only regret

Our only regret is that the town of Tenchong 腾冲 had also just opened, but we didn’t know. At that time, Tenchong still preserved its historic architecture, which apparently has now vanished under the sledgehammer. A pity.