Lijiang Today

When the Lijiang Express (a far cry from the old rust bucket that hauled us there from Panzhihua in 1991)- large leather armchairs, seatbelts, hostesses and blaring TV – pulled into modern Lijiang we feared the worst: we had arrived in what seemed to be a vast expanse of empty roads, half-finished concrete buildings, monstrous new hotels and souvenir shops… Was this going to be the Dali nightmare all over again? Adam most eloquently expresses his feelings on the over-exploitation of that once lovely village on our blog Holachina.blog » The Death of Dali / Shangri-La Tourism What happens when all of China and the world want to visit a small town? .

we were shocked by the mayhem

A friendly Naxi taxi driver drove us to the area near the waterwheels, which marks the entrance to the Old City. Immediately, we were shocked by the mayhem: we saw scores of Chinese girls dressed in fake Naxi costumes, tourist ponies, photographers, touts and, of course, hundreds of tourists milling about, or trailing after their megaphone-toting, flag-waving guides!

We quickly turned into one of the narrow, cobbled streets, these days lined with souvenir shops, and went in search of affordable accommodation, which we eventually found at the fairly atmospheric Old Town Inn.

The whole scene was incredible distasteful

When we emerged again in the evening, we found that the streets and canals were lit by romantic red lanterns. Unfortunately, it wasn’t long before the mellow ambience created by the lanterns was completely shattered by the thumping music emanating from a group of disco bars. Inside, there were girls dancing on the tables, surrounded by inanely clapping and cheering men leering at them through half empty Maotai bottles and their steamed up glasses. The whole scene was incredible distasteful and entirely out of place in a traditional village with a sensitive minority culture, such as Lijiang.

Remnants of the Old Lijiang

Not all had gone

Fortunately, as we discovered the next day, Lijiang hasn’t lost all its charm yet. We got up very early and explored the semi-deserted streets, just as the first shop keepers were removing the wooden shutters from their establishments. On the pavements, little stalls serving traditional breakfasts, mostly for the locals, had been set up. Strolling among scores of Naxi ladies, many of them in traditional costume, we made our way to the market.

The morning market is the centrepiece

This market, the centrepiece of which is formed by several large wooden halls, is a vibrant and authentic affaire. There are lots of the usual vegetables, mushrooms and grizzly meats (dog lovers be warned: the skin of those unfortunate doggies selected to be eaten is crisped by a blow torch), but also a couple of fascinating stalls selling cheeses and cured ham, a surprising element of the Naxi diet that reminded us of Spain.

T-shaped sheepskin

Exhausted from our wanderings, we spotted a little hole-in-the-wall restaurant with an excellent location for people watching. From there, we were able to really study the Naxi female costume. We noticed that the ladies wear long, slightly pleated aprons over their trousers, and blue cloth caps of the type mostly associated with men, in particular sailors. But by far the most interesting aspect of their attire is the T-shaped sheepskin they wear on their back, woolly side in, to protect themselves from the eternal baskets they are always carrying. The top part of this sheepskin is covered in dark cloth, like a little pelerine, and embroidered with six, colourful circles.

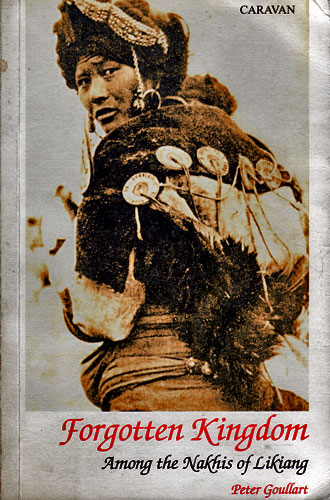

Sitting down among the locals, savouring a couple of excellent mushroom dishes, washed down with a cup of locally brewed jiu (alcohol), we could almost fancy ourselves in Madame Yee’s wine-shop, that fine Lijiang establishment, immortalised in Peter Goullart’s book ‘Forgotten Kingdom- Among the Nakhis of Likiang’.

‘Forgotten Kingdom’

‘Forgotten Kingdom’

‘Forgotten Kingdom’ is the fascinating account of Peter Goullart’s 10-year stay in Lijiang, between 1939 and 1949, where he worked setting up government-sponsored co-operatives. Goullart is an excellent observer who offers all kinds of details and reflections on local customs, anecdotes and juicy bits of gossip. Interestingly, Goullart claims Lijiang was already on its way to losing its unspoilt, authentic character as early as 1949, as different Chinese political factions fought over its control, just before the culmination of the Communist take- over.

In fact, we were so gripped and inspired by his book that we spontaneously decided to revisit Lijiang. On our subsequent explorations we were mostly guided by his third chapter, The Market and Wine Shops of Likiang, though we never found the real yin jiu, oryintsieu, as it is spelled in the book.

If you are interested, a paper back version by Caravan Press is readily available in the area. Check your copy though, as ours was missing several pages!