Arhats (or Luohan,十八羅漢, in Chinese)

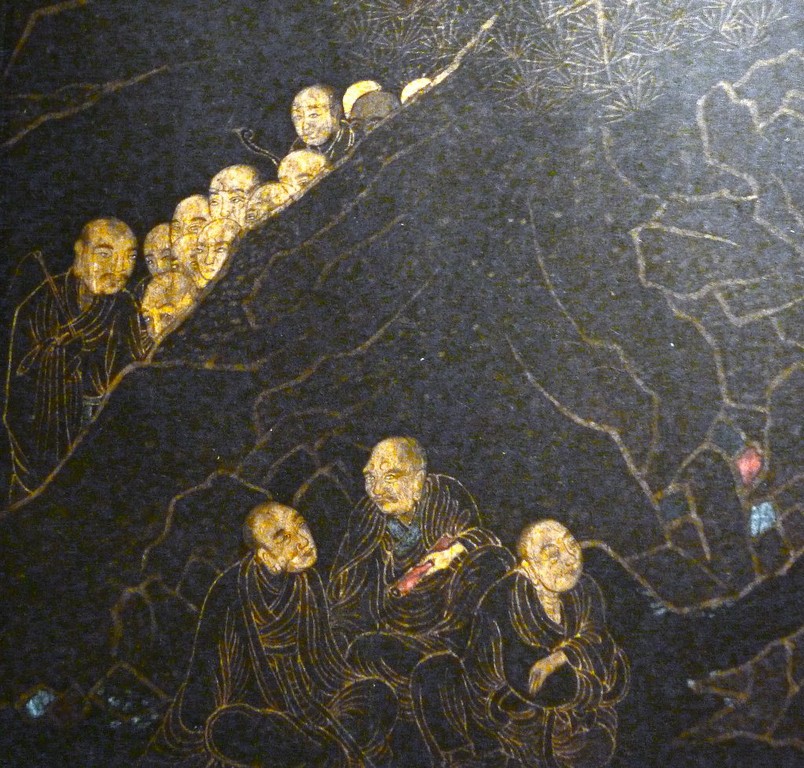

Arhats: China’s Enlightened Gentlemen:If you love visiting Chinese Buddhist temples, as we do, you will probably be familiar with the term Arhat, as colourful paintings and sculptures of these monk-like beings, shown in groups of 16, 18, or even 500, are a common feature of temple halls.

Arhats: China’s Enlightened Gentlemen: who or what exactly are Arhats?

But, who or what exactly are Arhats? The word Arhat comes from Sanskrit and means ‘one who is worthy’; in Buddhism, that is a person who has gained insight into the true nature of existence and has achieved Nirvana (spiritual enlightenment). In this way, Arhats, who are usually monks or nuns, manage to free themselves from ignorance, excitability, ambition, and the desire for existence, so that they will not be reborn.

Although this definition seems fairly clear, we have to bear in mind that the concept of the Arhat has changed over the centuries, and varies between different schools of Buddhism.

Whereas in the Theravada tradition becoming an Arhat is considered to be the proper goal of a Buddhist, Mahayana Buddhism uses the term for people far advanced along the path of Enlightenment, but who may not have reached full Buddhahood.

Moreover, they believe that the Bodhisattva is a higher goal of perfection. Although the ultimate purpose of the Bodhisattva is to achieve enlightenment and become a Buddha, they are willing to postpone their entrance into Nirvana in order to remain in the world and save other beings from suffering.

This difference of interpretation seems to be one of the fundamental divergences between the Theravada and Mahayana traditions. However, even in Mahayana Buddhism, the accomplishments of Arhats are recognized and celebrated, mainly because they have transcended the mundane world.

The Chinese Buddhist tradition and Arhats

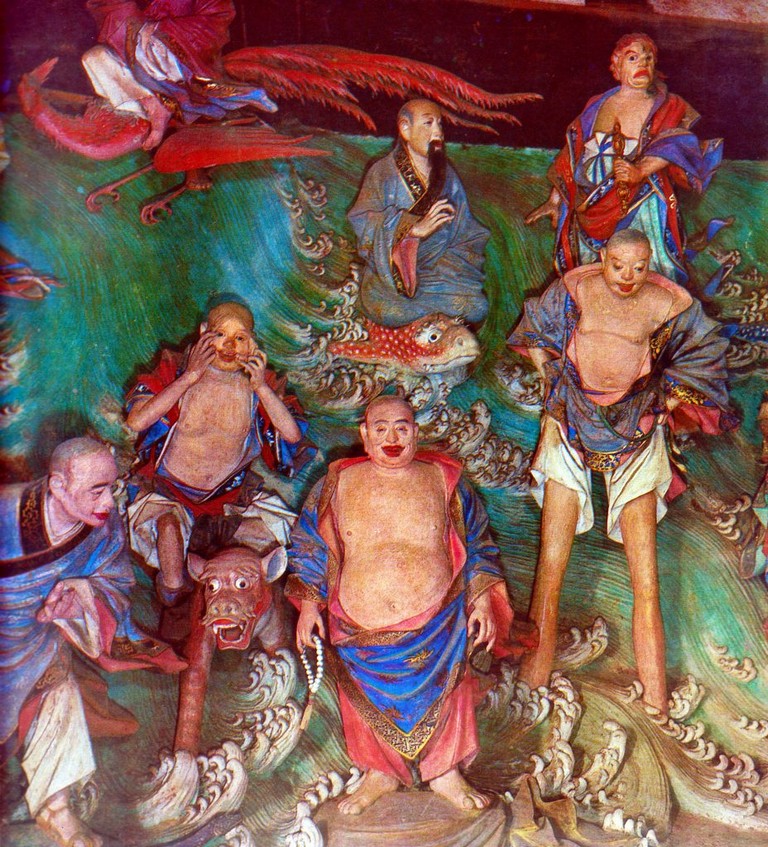

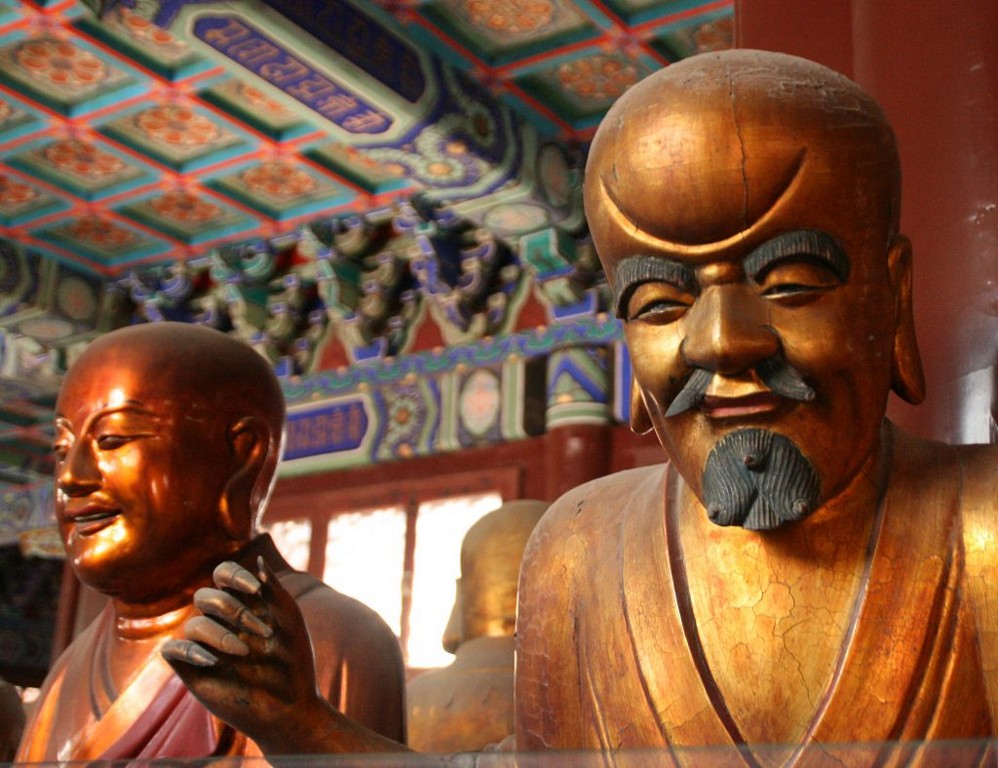

In the Chinese Buddhist tradition, Arhats are usually depicted in groups of 16 and later 18; all with their own names and personalities: Deer Sitting, Happy, Raised Bowl, Raised Pagoda, Meditating, Oversea, Elephant Riding, Laughing Lion, Open Heart, Raised Hand, Thinking, Scratched Ear, Calico Bag, Plantain, Long Eyebrow, Doorman, Taming Dragon and Taming Tiger. Interestingly, the cult of the 18 Arhats only became popular in China, while other Buddhist countries such as Japan continue to revere just 16.

These 16 or 18 represent the closest disciples of the Buddha who were chosen by him to remain in this world and not to enter nirvana until the coming of the next Buddha, in order to give people something / someone to worship. We can think of them as the Buddhist equivalents of Christian saints, or apostles.

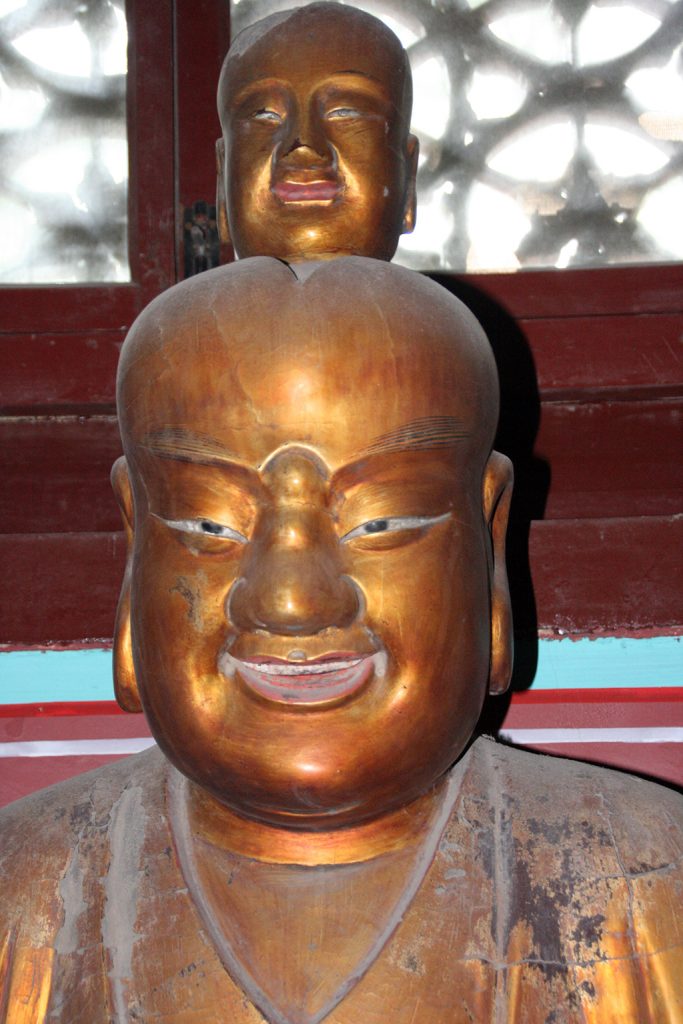

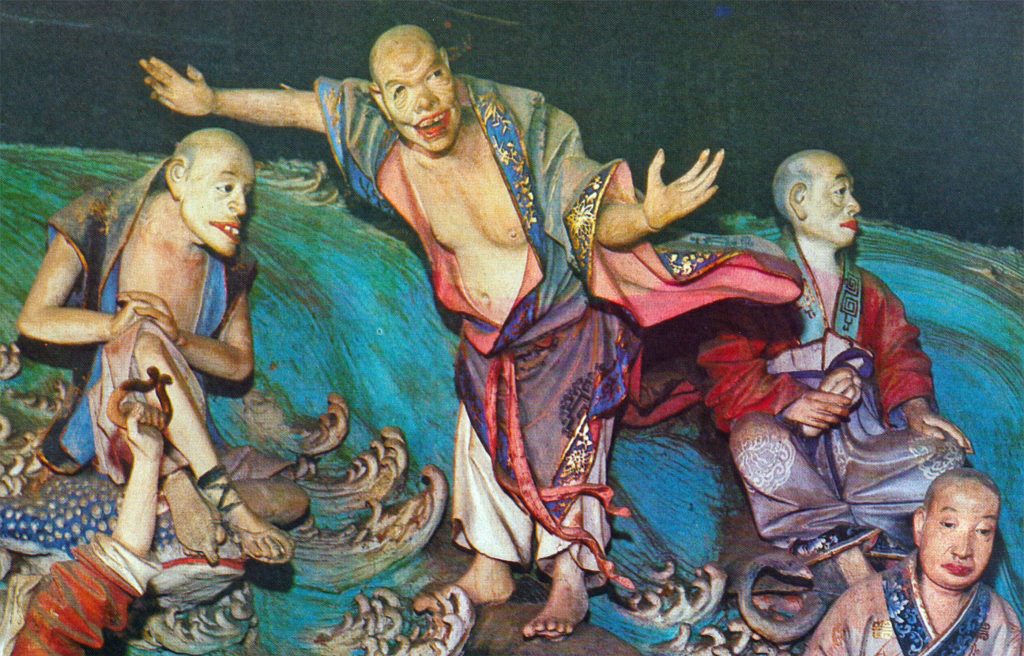

Leaving aside the tricky question of exactly how holy or perfect the Arhats are, what has always puzzled us is the way they are portrayed: Arhat paintings and sculptures are often sinister, ludicrous, grotesque, or just downright ugly. Of course, from a Western point of view this is extremely shocking, because we associate ugliness with evil and beauty with goodness: just think of the idealized images of Christian saints and angels. And it has taken us a long time to find information to shed some light on this mystery. So, here is what we have come up with.

The Influence of Guanxiu (貫休 / Guànxiū)

Apparently, the first famous portraits of Arhats were painted by the Chinese monk, painter, poet, and calligrapher Guanxiu (貫休 / Guànxiū) in 891 CE. Guanxiu started his career during the Tang dynasty, in what has often been described as a golden age for literature and the arts.

However, the Tang dynasty had been in decline for some time and eventually collapsed in 907, which meant that many artists lost their patrons.

For this reason, Guanxiu fled to the city of Chengdu in 901, where something like a miniature Tang court still existed and where Wang Jian, the founding emperor of the Former Shu (one of the Ten Kingdoms formed during the chaotic period between the rules of the Tang and Song dynasties) took him in and gave him the honorific title Great Master of the Chan Moon.

The Legend Of Guanxiu’s painting skills

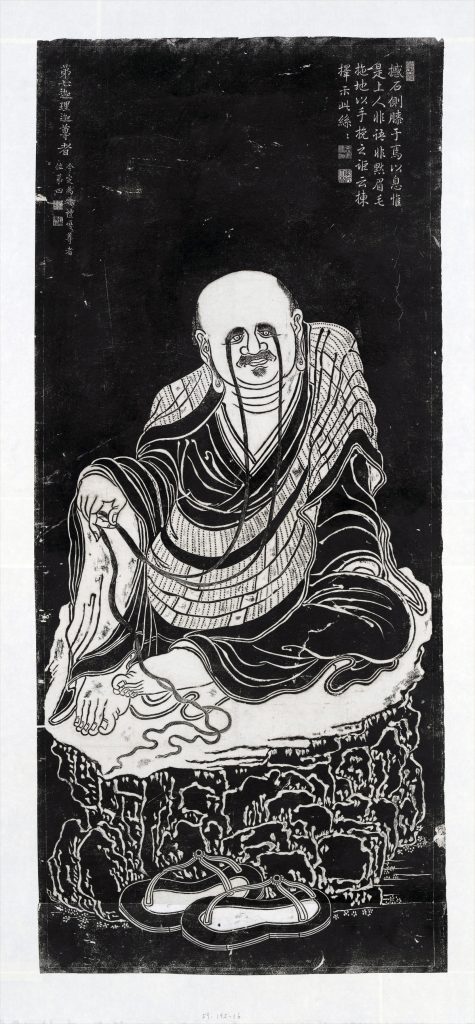

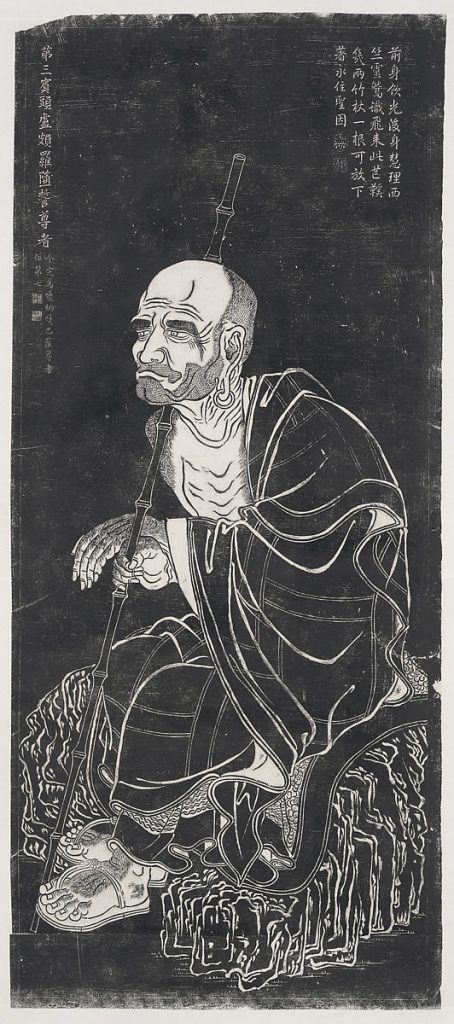

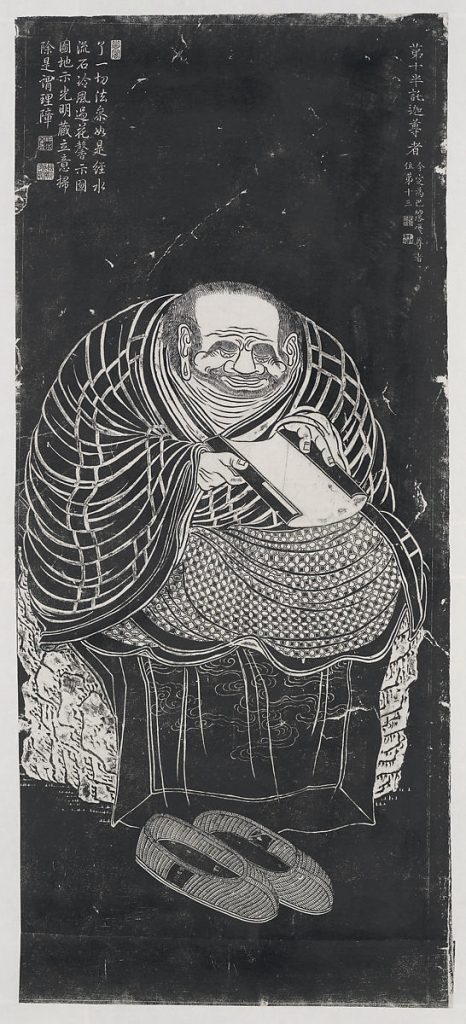

Legend has it that the Arhats had heard about Guanxiu’s painting skills and appeared to him in a dream and asked him to paint their portraits. In the paintings, the Arhats are portrayed as foreigners with bushy eyebrows, large eyes, hanging cheeks and high noses. Moreover, they look unkempt, shabby and eccentric. By showing them like this, it seems that Guanxiu wanted to emphasize that they were like outsiders, vagabonds and beggars; beings who had left all worldly desires behind.

Following Guanxiu’s example, the Chan painters, as they became known, continued representing Arhats with exaggerated and almost perverse features, accentuating their decrepit, skeletal bodies and bony faces, as well as their advanced age.

Although Guanxiu’s portraits remained extremely important in Chinese Buddhist iconography, over time, the Arhats started to look less foreign, though no less eccentric.

Art historian Max Loehr on Guanxiu’s Arhats

According to art historian Max Loehr, Guanxiu’s Arhats represent the physical incarnation of the persecution Buddhists suffered in eighth-century China; a persecution that almost wiped out the Buddhist establishment. Their tormented faces make the Arhats look like survivors of death and destruction.

However, given that Chinese artists had been painting and sculpting expressive and powerful Arhats for centuries, it seems unlikely that either Guanxiu’s uncommon talent or religious persecution alone can account for the grotesque images that fascinate us so. Cultural differences between East and West must play a part too.

In a fascinating blog post dating from 2009, the Argentinian cartoonist and illustrator Enrique (Quique) Alcatena, who apparently finds much of his inspiration in mythology, explains that in Asian cultures the ferocious, wild looks of the Arhats are recognized as a symbol of the superhuman strength of these illuminated beings and their determination to crush darkness and evil.

In fact, the Arhats need to look fearsome if they want to inspire fear in devils and other forces of evil and keep them at bay.

The Destruction of the Shengyin Temple

Guanxiu donated his paintings to the Shengyin Temple in Qiantang (in present day Hangzhou) where they were preserved with great care and ceremonious respect. The Shengyin Temple was destroyed duing the Taiping Rebellion (1850 1864). However, the Qianlong Emperor (Qing Dynasty) , who visted the Shengyin Temple in 1757, was so impressed by the paintings that he managed to have copies made and what exist now are those copies and copies (rubbings) of those copies.

Another set of sixteen Arhats is preserved in the Japanese Imperial Household Collection. This collection bears an inscription dated to 894. It states Guanxiu began the set while living in Lanxi, Zhejiang province.