Bakong Tibetan Scripture Printing Lamasery Dege is not the only reason to come to this remote area of China’s Sichuan Province. There are plenty of other things to see and do. It is however, the end of the road for non- Chinese travellers. Tibet is so close but yet so far.

A bit of a Shock on arrival

The town, we must admit, came as a bit of a shock at first. Having travelled so far, to such a remote place, only to find ourselves in yet another dusty white-tile frontier town, full of hooting traffic, smoking exhausts and blaring radios was not quite what we were expecting.

The only hotel in town had even incorporated a karaoke cum disco in its rapidly deteriorating “new wing”: even though this part of the hotel was only one or two years old, there were cigarette burns in the carpets, peanut shells and pips littering the floor, and stains everywhere.

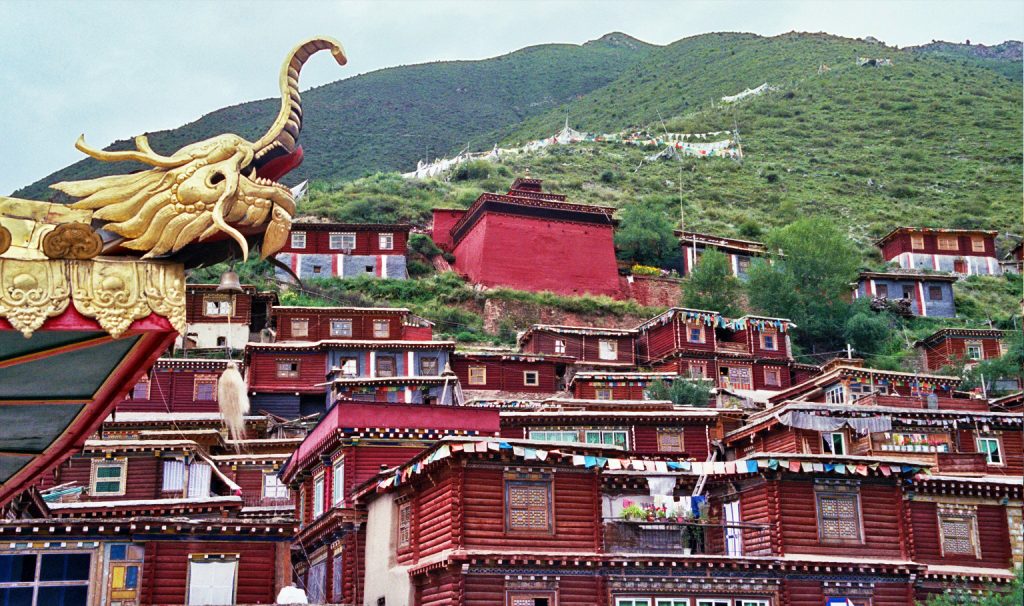

It wasn’t until the next day that we discovered the delights of the small old town, which houses a number of interesting and beautiful temples, converting Dege in a vibrant place, dominated by the wine-red robes of the monks and the exotic attire of the numerous pilgrims, circumambulating the temples and shrines.

Bakong Tibetan Scripture Printing Lamasery Dege

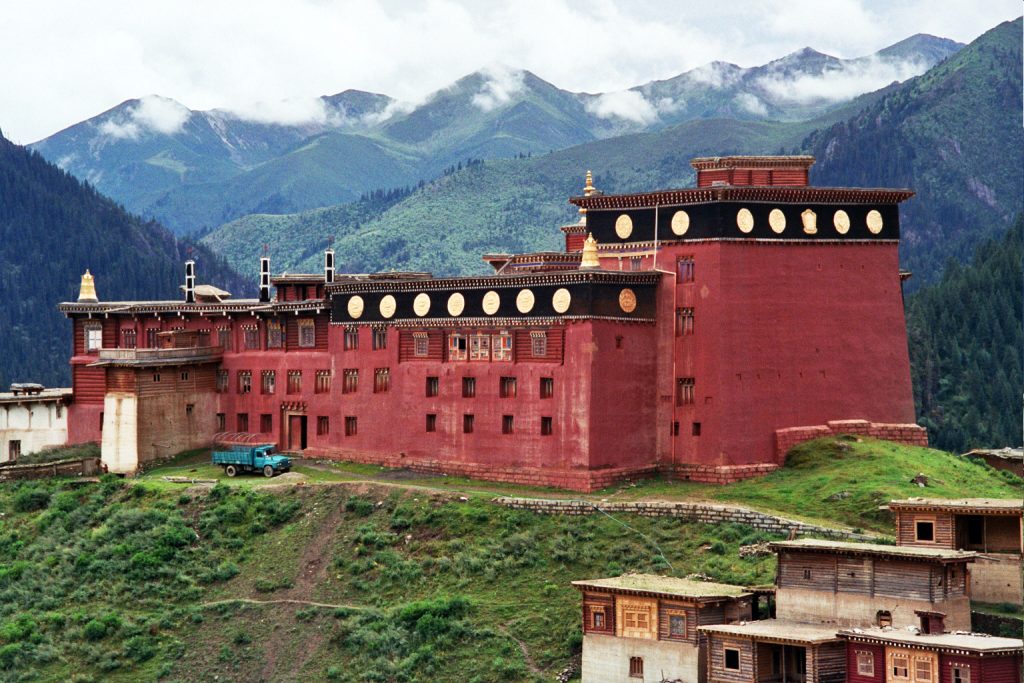

The jewel in Dege’s crown is undoubtedly the Bakong Scripture Printing Lamasery.

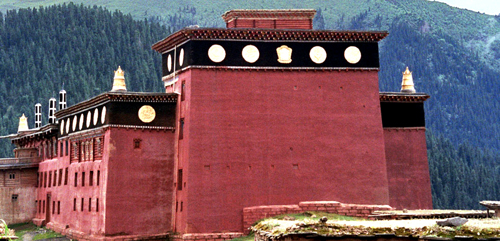

This monastery, whose printing press was built in 1729 and is still operative, holds an important part of Tibet’s history and heritage. The building itself is quite imposing; its walls are painted brick-red, with a decorative rim of dark-brown twigs pressed into one solid layer, while the flat roofs are topped by golden birds, bells and turrets.

Groups of wild-looking pilgrims with unkempt long braids and wrapped in Tibetan greatcoats move clockwise around the outside.

Everything Handmade

Nearby, groups of monastery workers, most of them women, their index fingers protected by leather thimbles, are busy making wood pulp from thin strips of shredded wood, while others are wetting finished sheets of paper to soften them and prepare them for use.

Inside the print, nothing much has changed for centuries: there are still over a 100 workers, more than 210,000 stored wood-block printing plates, and no mechanization to speak of; so far the monastery has even avoided electricity for fear of fire.

The wood-block texts

The wood-block texts in the library cum storeroom include works on astronomy, Tibetan traditional medicine, geography and music, as well as important treatises on Buddhism. The most valuable item in the collection consists of 555 blocks, detailing the history of Buddhism in India, in Hindu, Urdu and Tibetan.

The oldest blocks are carved into precious woods that are no longer available. In the past, carvers were only allowed to produce one line of text a day, for reasons of clarity.

At the end of the day, their work would be remunerated by putting gold dust on the blocks and then wiping it off. All the gold that remained in the openings, lines and spaces was for the carvers. Obviously, the deeper and clearer they carved, the more they would earn.

The printers

The printers, who are mostly young men, work in groups of three, moving like well-oiled cogs in a machine: one of them places the paper in the wooden contraption used for printing and holds it in place, the other one inks the wood-block and presses it down on the paper.

The third one is in charge of fetching the correct blocks, collecting and sorting the finished prints, as well as plying the printers with tea. The printed text appears quickly, at a speed of about one page every four seconds.

However, given that many of the sacred texts, such as the Tengzur, a 46,521 page collection of 14th-century scholastic commentaries on Buddhism, are extremely long, it can take one team of workers roughly a month to produce just one copy.

Bakong Tibetan Scripture Printing Lamasery Dege

In the open-air courtyards, which are surrounded by beautifully painted columns and galleries, older men are busy washing the ink off used printing blocks, mixing paint, or proofreading and checking finished texts and storing them away.

Just by being there and observing the process, you can appreciate how fragile Tibet’s heritage is. That the monastery survived the ravages of the cultural revolution is a miracle in itself!

Moreover, the fact that the whole interior of the building, the library and its irreplaceable collection of printing blocks are made of wood, make it extremely vulnerable to fire. One careless mistake or loose spark and it could all go up in smoke.

The vulnerability of the monastery is one of the reasons you can only visit by guided tour. Unfortunately, most of the guides are elderly men with only the most rudimentary knowledge of Mandarin, who will herd you through far too quickly.

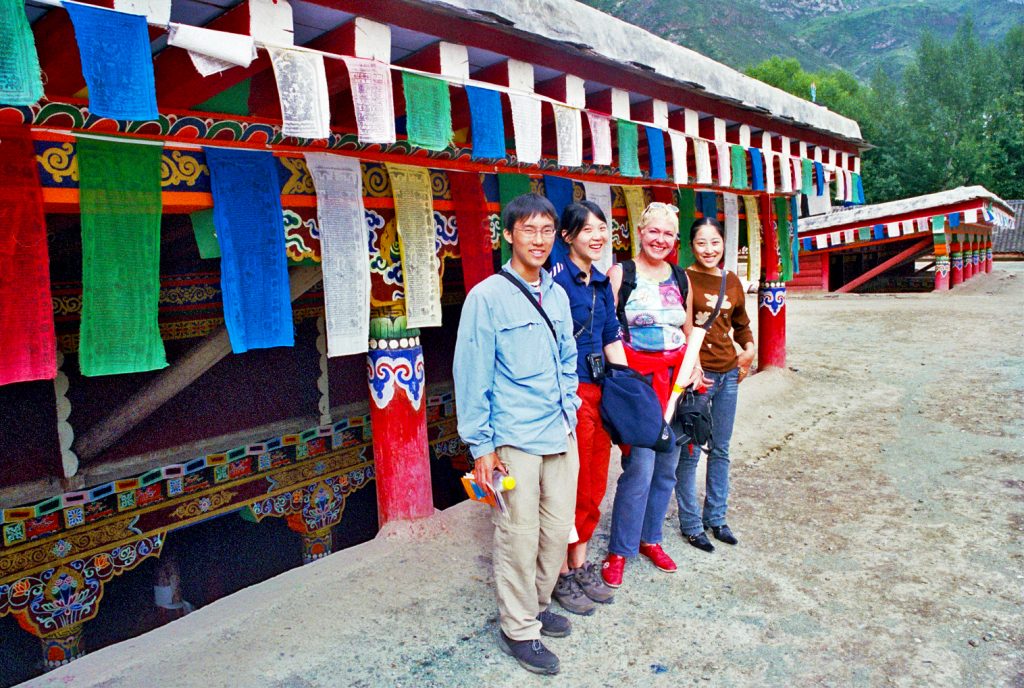

An Amazing Guide

However, there are exceptions. We were extremely lucky to be guided by a lovely young Tibetan girl who had actually studied Tibetan culture at a Minorities University and who was completely dedicated to her work.

She explained that most of the print workers are locals who spend their whole life there, starting with the physically taxing work of printing itself, and gradually moving on to lighter tasks as they get older.

They all need to be literate, up to an extent, in order to carry out their tasks well. In winter, when work at the print comes to a standstill, due to the bitter cold which freezes the ink, and makes the printers’ hands clumsy, many of them spend time at their family farms.

We spent over two hours with her, eventually going up to the top floor where a few ancient monks were making coloured picture prints on cloth and valuable parchment, of which we purchased several, and finally climbing onto the roof, from where there are splendid views over the town. Printing blocks that have been washed are covered in yak butter and laid out to dry here.

Other Monasteries in Dege

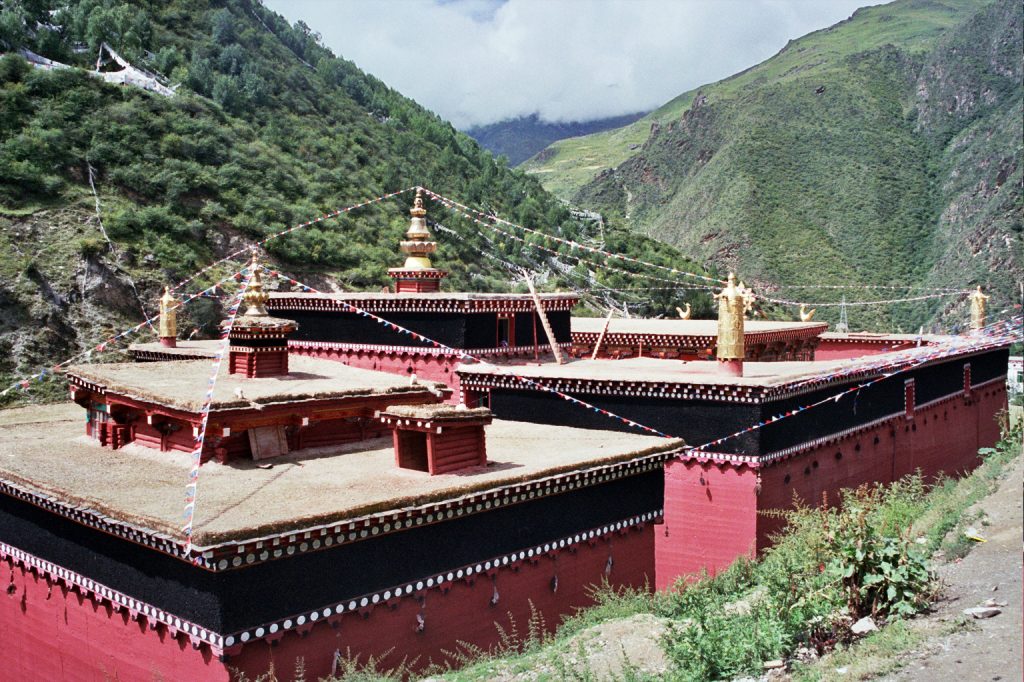

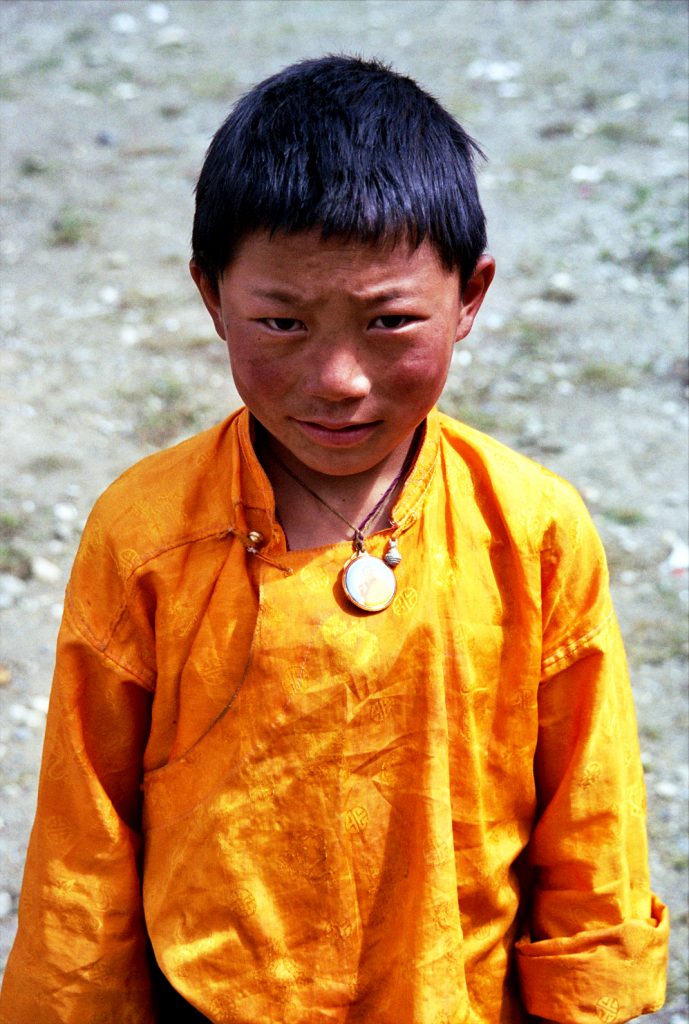

Just beyond the Bakong monastery, there are several other lamaseries that are well worth exploring: there are temples, residential blocks set in flower gardens, communal kitchens and primitive outdoor latrines. Groups of monks in flowing robes and child novices in yellow tunics and trousers move between the buildings.

At mealtimes you can see them with their bowls and utensils in hand, lining up at the kitchens or dining halls. Overall, they are extremely friendly and welcoming and don’t seem to mind posing for the odd photo, as long as you don’t overdo it.

Dege Ganchen Baden Lundru Ding Temple

One of the monasteries, the Dege Ganchen Baden Lundru Ding Temple (though this seems to be just one of many names given to it), has a particularly imposing main hall with tall pillars, colourful wall hangings and thankas, big painted drums and large but serene statues of the Buddha.

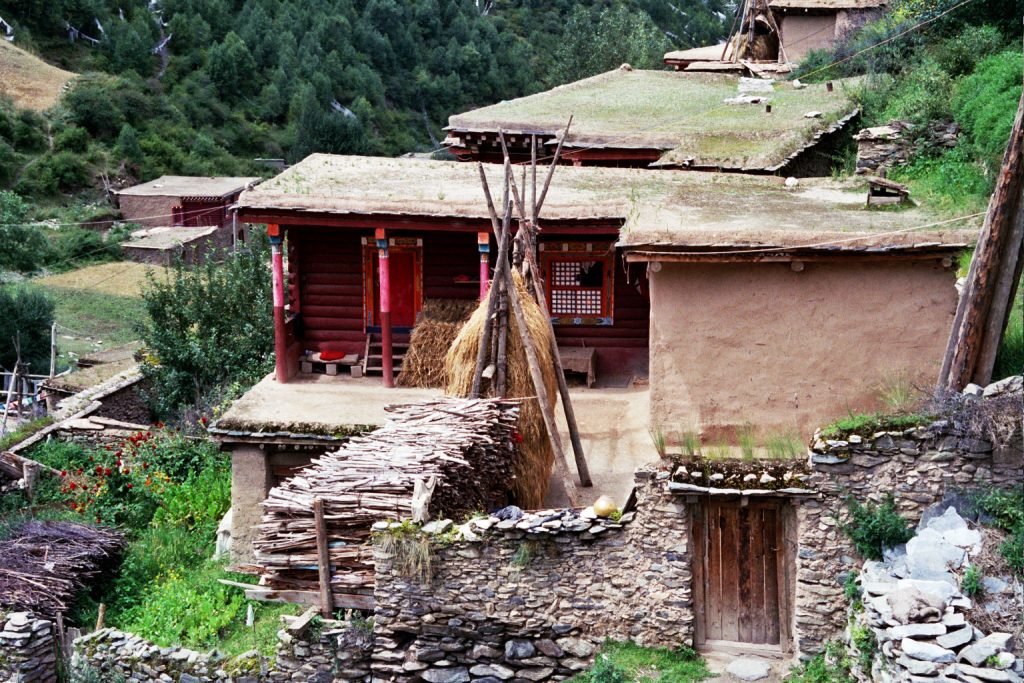

Where the monastic town ends, an idyllic rustic village takes over, with Tibetan farmsteads, haystacks and vegetable patches. Beyond that, fertile fields, small streams and an endless expanse of countryside.

Dege Practicalities:

Accommodation:

At the time of writing, the best hotel in town was the “Que Er Shan”, opposite the “Dege Binguan” and run by the same management. In the “Dege Binguan”, double rooms are only Yuan 50, with pay-showers outside, while the “Que Er Shan” charges Yuan 180, no haggling admitted. Despite the slightly run-down feel of the hotel, rooms are quite large and bright, beds are comfy and the showers are piping hot at night. Just make sure your room isn’t too close to the Karaoke.

Food:

There are plenty of small, hole-in-the-wall type eateries in town, some of the best run by Han-Chinese and specialising in Sichuan food. Up on a sloping street, just above the hotel, is the “Rhong Zhong Bros Restaurant”, run by a nice young couple from Chengdu; its specialty are potato pancakes and they have a basic menu in English. Other options include Tibetan and Muslim food.

Communications:

Dege even boasts an upstairs Internet café, on the main street leading to the Bakong monastery, on the left-hand side as you are heading towards the monastery, which is popular with the younger generation. Keep your eyes open for pickpockets though.

Excursions:

The spectacular and remote Palpung Monastery (click here)

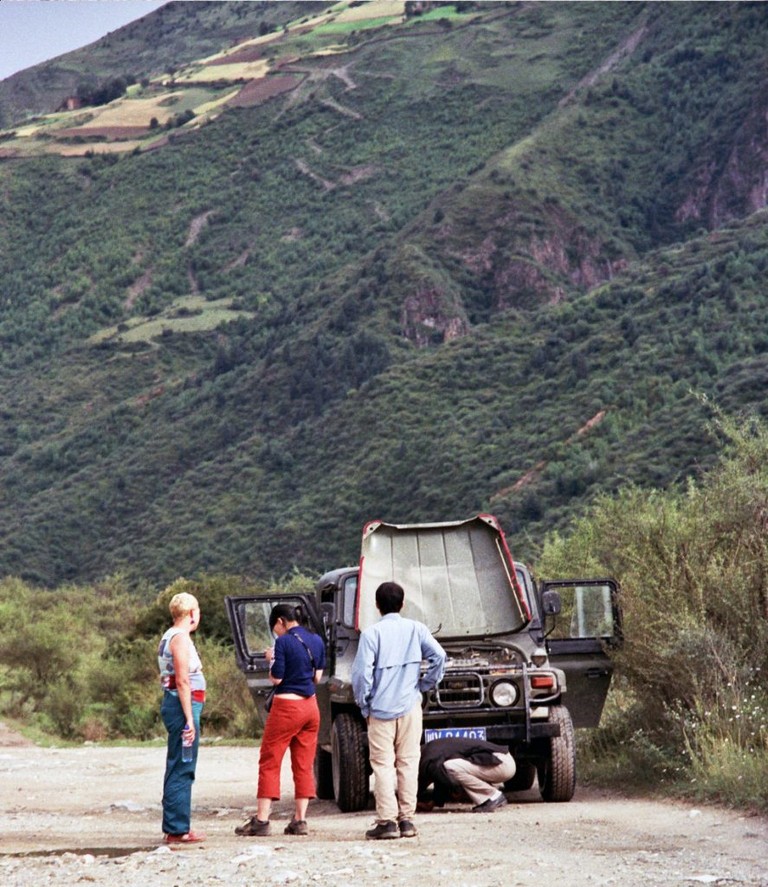

The manager of the “Que Er Shan” can help you to rent vehicles for excursions further afield. We paid Yuan 450 for an old jeep, plus driver for the day. A much more comfortable brand-new Mitsubishi would have cost us Yuan 1,000. In retrospect, given the state of the roads, plus the state of our backsides after the ride, the Mitsubishi would have been worth it.

Transport:

The Dege bus station is nothing like its Ganzi counterpart. Every time we tried to buy tickets, we had found it closed. Eventually, we asked the hotel manager of the “Que Er Shan” to book the tickets for us. Daily buses for Ganzi leave around 7 o’clock in the morning, and they are mostly old beasts. Make sure you have a reserved seat as the bus does fill up.

After Dege:

There is a daily bus to Chamdo in Tibet 7.00 but as the Tibetan border is still closed to individual travellers, your options for continuing your journey are the following:

To Baiyu 白玉

If you want to avoid risking the Chola Pass for a second time,you can hire a vehicle or share a mini bus from Dege to the Monastery town of Baiyu. The road follows the Jinsha Rvier with Tibet proper on the other side. The must see sight here is the Pelyul Gompa 白玉寺 (Baiyu Si) which is also a Tibetan printing monastery.

In Baiyu there is accommodation, food, and onward travel to Ganzi. If you set out early enough with your own transport (jeep), you can take in the spectacular and remote Palpung Monastery (click here).

Backtrack

- You can backtrack to Ganzi and eventually make your way back to Chengdu from there. There is even a direct bus linking Ganzi to Chengdu, though we wouldn’t recommend it.

- This bus leaves Ganzi at 6.15 in the morning and takes 11 hours to get to Kanding, driving steadily and without any delays. However, once you get past Kanding, night falls and road conditions worsen. We found ourselves driving down pitch-black windy mountain roads, overtaking vehicles on blind corners and going faster than even modern passenger cars. Terrified, we repeatedly shouted at the driver to slow down, to the amusement of the Chinese passengers, who didn’t seem to share our sense of doom.

- Eventually, after 19 hours on the bus, the last 7 of which were extremely stressful, we pulled in at Chengdu bus station. If we ever had to do it again, we would definitely stop for the night in Kanding.

Update

- The road between Kangding and Chengdu is now is much improved and the journey a breeze.

To Yushu / Serxu

- Secondly, you can backtrack from Dege to Manigango and change buses, or go all the way to Ganzi if you want to be sure of a seat, or don’t fancy spending a night in Manigango.

- Next you can head for Serxu, and then Yushu in Qinghai province. From there, you can make your way slowly to Xining, the capital of the province. There are some important monasteries close to Xining, such as Tongren and Ta Er Si, and the city is linked by rail to Lanzhou, the capital of Gansu province. The journey only takes 4 hours on a fast train.

- Finally, you might want to continue your journey by moving into Yunnan province. In order to do this, you need to get back to Kanding first. From there, you make your way to Litang, then Xiangcheng – where you most likely will have to spend the night – and eventually Zhongdian in Yunnan.